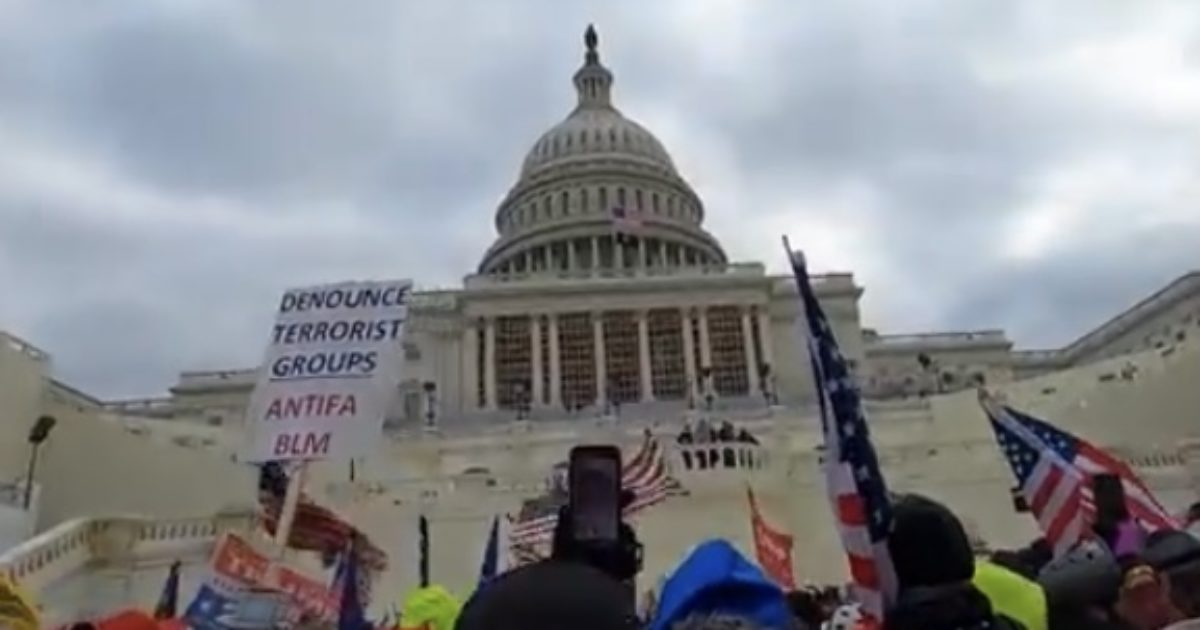

The FBI’s investigation into J6 utilized controversial geofence warrants, court records show.

“A filing in the case of one of the January 6 suspects, David Rhine, shows that Google initially identified 5,723 devices as being in or near the US Capitol during the riot,” Wired reports.

“Around 900 people have so far been charged with offenses relating to the siege.”

Rhine’s case, where he argues the geofence warrants as overbroad and unconstitutional, could set a precedent for how law enforcement can utilize location history.

The FBI got a massive geofence warrant for its Jan 6 investigation, compelling Google to identify 5,723 devices near the capitol that day – the case could set a precedent for how law enforcement leverage location history. https://t.co/qmkUXhgPxp

— Avi Asher-Schapiro (@AASchapiro) November 29, 2022

Incredible 4th Amendment case – geofence warrants. Absolutely a search; which pulled the data of police and journalists as well. WAY too broad. https://t.co/6Djju5FuHn

— Jason Roberge 🔴 (@JasonRobergeVA) November 30, 2022

Some interesting details. The warrant captured 70 devices that only reported their location history to #Google later that evening, or the next day. These phones were likely in airplane mode during the riot but still stored their GPS position.

— Mark Harris 🇺🇦 (@meharris) November 28, 2022

The geofence warrant was cited in charging documents of dozens of the 900+ people arrested since the Jan 6 attacks. One suspect is trying to get the warrants thrown out as unconstituional. If successful, it could jeopardize multiple cases. https://t.co/AiCGPyZ8MJ

— Mark Harris 🇺🇦 (@meharris) November 28, 2022

Wired provided further details about geofence search warrants:

Geofence search warrants are intended to locate anyone in a given area using digital services. Because Google’s Location History system is both powerful and widely used, the company is served about 10,000 geofence warrants in the US each year. Location History leverages GPS, Wi-Fi, and Bluetooth signals to pinpoint a phone within a few yards. Although the final location is still subject to some uncertainty, it is usually much more precise than triangulating signals from cell towers. Location History is turned off by default, but around a third of Google users switch it on, enabling services like real-time traffic prediction.

The geofence warrants served on Google shortly after the riot remained sealed. But lawyers for Rhine, a Washington man accused of various federal crimes on January 6, recently filed a motion to suppress the geofence evidence. The motion, which details the warrant’s process and scale, was first reported by journalist Marcy Wheeler on her blog, Emptywheel.

In a statement, a Google spokesperson defended the company’s handling of geofence warrants.

In the second step, the FBI asked Google for a list of devices that were present at the Capitol from 12 pm to 12:15 pm on January 6, and from 9 pm to 9:15 pm. As there were no rioters in the Capitol during those times, these devices likely belonged to congressional members or staff, police, and other people authorized to be there. Over 200 such phones were excluded from the initial list, reducing its total to 5,518.

For the final step, the government sought subscriber information, including phone numbers, Google accounts, and email addresses, for two groups of users. The first was for devices that appeared to have been entirely within the geofence, to about a 70 percent probability. The second was any devices for which the Location History was deleted between January 6 and January 13.

From this, in early May 2021, the FBI received identifying details for 1,535 users, as well as detailed maps showing how their phones moved through the Capitol and its grounds. Geofence evidence has so far been cited in over 100 charging documents from January 6. In nearly 50 cases, geofence data seems to have provided the initial identification of suspected rioters.

Rhine was first flagged to the FBI by tipsters who had heard that he had been inside the Capitol. But investigators only identified him in surveillance footage after they matched it against the precise geofence coordinates of his phone. His lawyer is now trying to get the geofence evidence thrown out on a number of grounds, including that it was overly broad in who it rounded up, and that Rhine had a constitutional expectation of privacy in his Google data.

“The government enlisted Google to search untold millions of unknown accounts in a massive fishing expedition,” the attorneys wrote. “Just a small amount of Location History can identify individuals … engaged in personal and protected activities (such as exercising their rights under the First Amendment). And as a result, a geofence warrant almost always involves intrusion into constitutionally protected areas.”

If the judge tosses the geofence evidence in the Rhine case, there is a chance that he and other suspects identified using it could walk free.

Matthew Tokson, a law professor and Fourth Amendment expert at the University of Utah, says there remains a high level of uncertainty around the whole idea of geofence warrants: “Some courts have said they are valid. Some have said they are overbroad and sweep up too many innocent people. We are still in the very early stages of this.”

The Rhine case will likely set a critical precedent on geofence search warrants and the dangerous Big Tech-Big Brother partnership threat to individual liberties.

The Federalist explained:

Google gave the feds the personal data of nearly 1,500 individuals based on cell phone location data indicating their presence near the Capitol complex on Jan. 6, 2021. The Department of Justice sought substantially more information, as well, according to a recent court filing, including data on Jan. 6 cell phone users wholly outside the Capitol. These facts, coupled with Google’s apparent disregard for the privacy rights of its customers, expose the potential for the government and Big Tech to collaboratively target political enemies.

In response to the riot that erupted inside the Capitol on Jan. 6, following a rally at the National Mall and a peaceful protest outside the Capitol, the Department of Justice launched a massive investigation seeking to identify and prosecute the individuals who committed crimes that day. Just a week after the Jan. 6 riot, “the government sought and was granted a ‘geofence’ warrant for data held by Google.”

A “geofence” warrant compels tech companies, such as Google, to provide the identity of individuals whose cell phones were physically located within a defined geographical area during a specific time period. The Jan. 6 warrant served on Google compelled the tech giant to search all accounts to identify devices that appeared physically present on Jan. 6 from 2:00 p.m. until 6:30 p.m. in the “target location.” The “target location” or the “geofence” covered by the warrant included the Capitol building and the area immediately surrounding it, which together covered about four acres of land.

In total, Google identified 5,723 “unique devices” that “were or could have been within the geofence during the relevant time period.” Of the 5,723 devices, the federal government then obtained a warrant forcing Google to provide “the phone number, google account, or other identifying information” for more than 1,500 cell phones that appeared located completely in the geofence area or in cases where the user had later deleted the location data.

How extensively the government used the data obtained from Google in investigating the riot is unclear, but the records eventually led the Department of Justice to charge David Rhine with four federal crimes: entering and remaining in a restricted building or grounds; disorderly and disruptive conduct in a restricted building or grounds; disorderly conduct in a Capitol building; and parading, demonstrating, or picketing in a Capitol building.

Rhine pleaded not guilty, and his public defender filed a motion to suppress the data obtained from Google connecting Rhine’s cell phone location to the Capitol, as well as any evidence the federal government obtained as a result of identifying Rhine through the geofence warrant. In his motion to suppress, Rhine argued that the geofence warrant was overbroad and lacking in particularity in violation of the Fourth Amendment.

Whether a geofence data search constitutes a “search” within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment remains hotly debated, and to date, only a few lower courts have addressed the issue. The handful of courts that have considered the issue have concluded the Fourth Amendment applies to requests for geofence data and thus the government must establish “probable cause” to obtain the data. And in upholding the geofence warrants in those cases, the courts have stressed the narrowness of the scope of the warrants at issue.

Join the conversation!

Please share your thoughts about this article below. We value your opinions, and would love to see you add to the discussion!