I stumbled upon something REALLY interesting today over on TruthSocial…

First of all, before we jump into those details, I have great news: TruthSocial is now open to EVERYONE!

If you have been waiting to log on, now is your time!

You can access through any web browser right from your computer!

Just go to https://truthsocial.com and create an account.

Once you’re up and running, Follow Me!

My page looks like this and I’m at https://truthsocial.com/@WeLoveTrumpWLT:

Ok, now let’s dig in to what I just found.

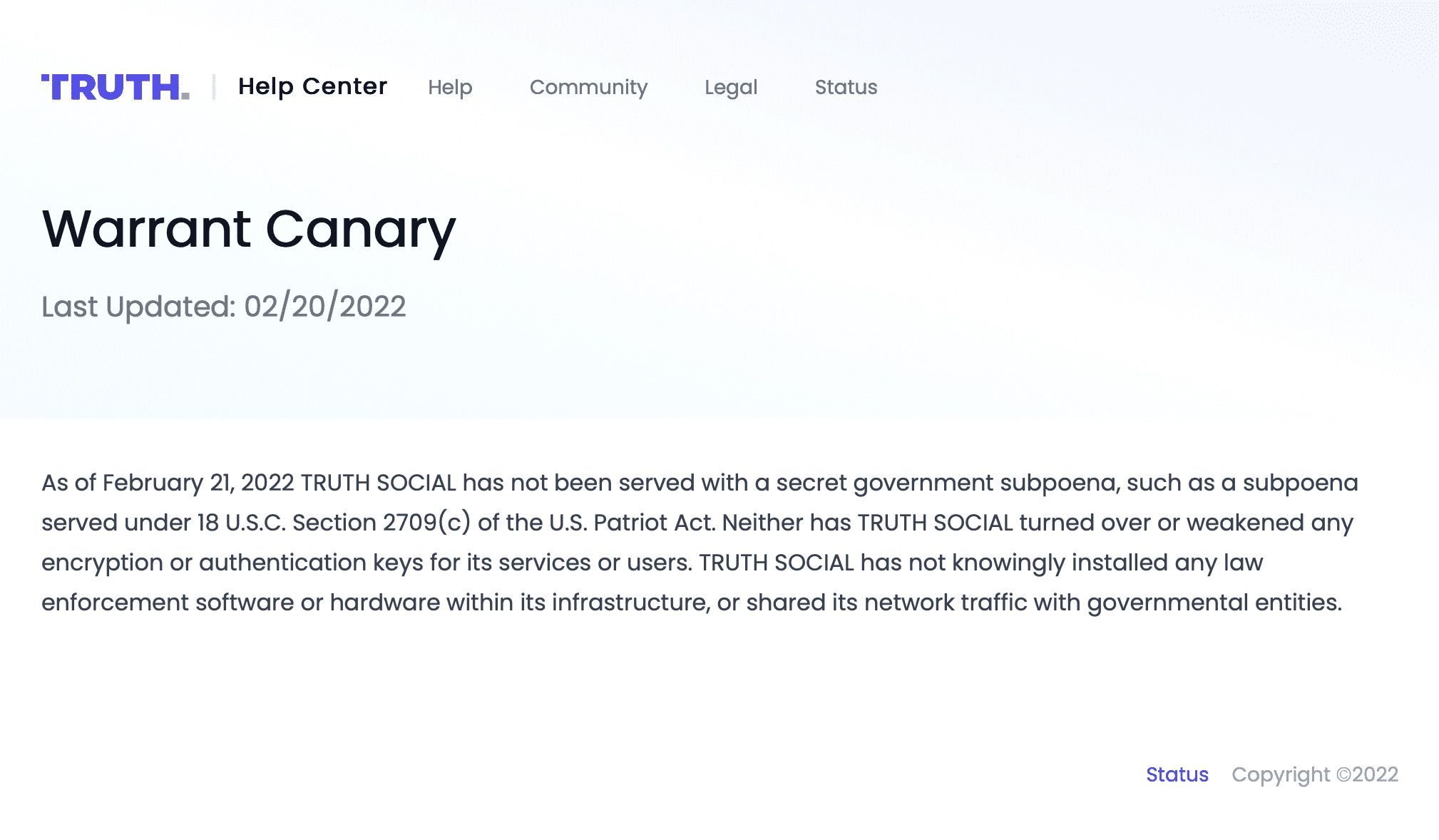

Have you heard of a “Warrant Canary”?

I had not.

But I was clicking around the new TruthSocial website and I saw a link at the bottom of one page that said Warrant Canary.

So I clicked it and got this message:

You can see it for yourself here: https://help.truthsocial.com/legal/warrant-canary/

I told you…VERY interesting!

You know who doesn’t have a statement like this?

Twitter.

Facebook.

Are you connecting the dots yet?

Oh my….

So what is a Warrant Canary anyway?

CloudFlare gives an explanation:

A warrant canary is a statement that declares that an organization has not taken certain actions or received certain requests for information from government or law enforcement authorities. Many services use warrant canaries to let users know how private their data is.

Some types of law enforcement and intelligence requests come with orders prohibiting organizations from disclosing that they have been received. However, by removing the corresponding warrant canary statement from their website (or wherever it is posted), organizations can indicate that they have received such a request.

Why is it called a “canary”? The term stems from the common “canary in the coal mine” analogy, which refers to the practice of bringing canaries down into mines to help indicate the presence of deadly gas. The gas was invisible and could not be smelled, but if the canary died, the miners would know the gas was present. Similarly, some government requests are “invisible” — they cannot be announced publicly. However, a missing warrant canary indicates that such a request exists, just as a canary’s death indicated the presence of deadly gas.

Warrant canary examples

One of the earliest examples of a warrant canary was a sign posted inside a library in the US state of Vermont in 2005. The sign simply read, “The FBI has not been here”; if the sign was taken down, the implication would be that the US Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) had accessed patrons’ records within that library.

Here is an example of a more sophisticated warrant canary for an online service: “Our company has never installed any law enforcement software or equipment anywhere on our network.” (See the Cloudflare warrant canaries section below for more examples.)

Twitter does NOT appear to have one.

Read this from JustSecurity:

On Friday, the Justice Department asked a federal district court to brush away a lawsuit filed in October by Twitter seeking greater freedom to publicly report on the numbers and types of surveillance requests it receives from the government, including the right to disclose that it has received “zero” of particular types of requests.

As Just Security readers may recall, Twitter filed a First Amendment suit challenging various aspects of the reporting regime the government and several major technology companies had established for the public accounting of national-security and law-enforcement surveillance requests received by those companies. Twitter was not one of the companies that agreed to the government’s reporting rules, which require firms to report the number of national-security requests received in large bands—a structure that Twitter contends obscures the transparency value of the reporting.

As I noted at the time of Twitter’s filing:

In one sense, . . . Twitter’s new suit is the latest in a line of cases challenging national-security-related gag orders under the First Amendment—a suit plainly special because of the plaintiff (a high-profile technology company, rather than an anonymous recipient of a surveillance request), but not entirely original as a species of litigation.

In another sense, though—and through a close reading of its complaint—Twitter’s suit is seeking to establish something quite different than the NSL cases: a constitutional right to truthfully inform its customers and the broader public that it has not received particular types of surveillance requests. In other words, Twitter is seeking judicial endorsement of its right to publish a “warrant canary.” What’s a warrant canary? As EFF explains, a warrant canary “is a colloquial term for a regularly published statement that a service provider has not received legal process that it would be prohibited from saying it had received. Once a service provider does receive legal process, the speech prohibition goes into place, and the canary statement is removed,” thereby informing the public that the process has been received.

The government’s new filing largely avoids the merits of Twitter’s complaint (and avoids entirely the novel “warrant canary” question teed up by the lawsuit), opting instead to challenge Twitter’s right to be in federal district court at all. The government first contends that the prevailing reporting structure—a January 2014 agreement between companies including Google, Yahoo, and Facebook referred to by the parties as the “DAG Letter”—is not a “final agency action” that would give rise to a claim under the Administrative Procedure Act. Moreover, the government argues, Twitter lacks standing because the DAG Letter does not impose any obligations on the company at all—rather, those obligations are incidental to secrecy obligations (read: “gag orders”) imposed by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court in its many orders and directives. Given that, as well as “settled principle[s] of comity and orderly judicial administration,” the government argues that Twitter’s challenge should be considered (if at all) under the “FISC’s specialized jurisdiction” over the orders it issues under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act.

It’s worth noting that the government has played this sort of double game before: In federal district-court litigations brought under the Freedom of Information Act by the American Civil Liberties Union and the Electronic Frontier Foundation seeking FISC documents related to Section 215, the government argued that the parties should address their complaints to the FISC itself. Yet years earlier, when the ACLU sought similar documents in the FISC, the government argued that FOIA was the proper avenue for relief.

And also from JustSecurity, here is more info (so interesting…):

This week, Twitter lobbed the latest volley in what has been both a fascinating and encouraging repositioning of technology companies vis-à-vis the U.S. government—a pivot that began last summer, in the wake of the initial startling revelations about the National Security Agency’s vast surveillance apparatus. On October 7, the company sued the government in federal court, arguing that the First Amendment prohibits the broad gag orders that the Department of Justice contends restricts what the company can say publicly about the national-security requests it receives—as well as those it doesn’t receive. As Twitter V.P. Ben Lee put it, “It’s our belief that we are entitled under the First Amendment to respond to our users’ concerns and to the statements of U.S. government officials by providing information about the scope of U.S. government surveillance—including what types of legal process have not been received. We should be free to do this in a meaningful way, rather than in broad, inexact ranges.”

The lawsuit has been praised by civil-liberties groups, like the American Civil Liberties Union and the Electronic Frontier Foundation, which for years have challenged the government’s use of gag orders to silence the recipients of surveillance requests in national-security investigations. (The ACLU won rulings against the “national security letter” gag-order provisions in 2005 and 2008 in the Second Circuit, and Wednesday the Ninth Circuit heardEFF’s challenge to the same provisions.) In one sense, then, Twitter’s new suit is the latest in a line of cases challenging national-security-related gag orders under the First Amendment—a suit plainly special because of the plaintiff (a high-profile technology company, rather than an anonymous recipient of a surveillance request), but not entirely original as a species of litigation.

In another sense, though—and through a close reading of its complaint—Twitter’s suit is seeking to establish something quite different than the NSL cases: a constitutional right to truthfully inform its customers and the broader public that it has not received particular types of surveillance requests. In other words, Twitter is seeking judicial endorsement of its right to publish a “warrant canary.” What’s a warrant canary? As EFF explains, a warrant canary “is a colloquial term for a regularly published statement that a service provider has not received legal process that it would be prohibited from saying it had received. Once a service provider does receive legal process, the speech prohibition goes into place, and the canary statement is removed,” thereby informing the public that the process has been received.

As I explain in this post, litigation surrounding the constitutionality of warrant canaries was inevitable once companies began to issue them—but Twitter’s suit has upended the posture of judicial review over the First Amendment issues in play in a very interesting way. In the expected warrant-canary case, a court would be faced with the question of whether the government can compel a lie—whether it can force a company to continue providing the public and its customers with information that has become factually incorrect (in order to, say, protect a particular ongoing national-security investigation). But Twitter’s suit presents a different question: whether a company can truthfully disclose to the public that it has not received a particular kind of request that, when served at some point in the future, would be accompanied by a gag order.

Before I dig further into the significance of Twitter’s latest move, a bit of background is in order.

1. Background to Warrant Canaries and Twitter’s Dilemma

In one of the more damning slides published by The Guardian and The Washington Post in their reporting about the NSA’s PRISM program in early June, 2013, the world learned that over a roughly five-year period, America’s largest technology companies—including Microsoft, Yahoo, Google, Facebook, AOL, and Apple (but not Twitter)—had become participants in a vast surveillance program operating under the FISA Amendments Act (“FAA”) that gave the NSA access (however “incidentally”) to the contents of Americans’ and others’ private data housed on those services. Some of those companies tried to push back almost immediately: Mark Zuckerberg posted to his personal Facebook page that he hadn’t even heard of PRISM until he read the name of the program in the newspaper; Google founder Larry Page said the same thing. Those claims turned out to be half-truths—the companies do participate in PRISM, but the founders simply didn’t know about that participation by name—but their animating sentiment has had staying power. The companies’ public rejection of NSA spying grew more confident over time. When the companies learned that the NSA was not just relying on their cooperation but was actively pilfering their data overseas, the companies decided to get tough. (As one Google engineer memorably wrote on his social-media page last fall, “Fuck these guys.”)

Thus began a dance that continues to this day. Caught red-handed—if not in reality, at least in perception—as willing handmaidens to the emerging and alarming U.S. surveillance state, and under threats to their bottom lines from the worldwide revulsion over their cooperation with the NSA’s activities, many Silicon Valley firms have begun to take their users’ privacy seriously. Collectively, they have jointly lobbied for surveillance reforms on Capitol Hill. Google implemented encryption protocols that protect emails in transit, both internally and when sent to users of other email services—and it blogged about it. Yahoo followed suit. Microsoft challenged an order issued under the Stored Communications Act for a foreign user’s emails stored in Ireland—and General Counsel Brad Smith took to The Wall Street Journal’s Op-Ed page to rally support for and attention to its efforts to check government surveillance on behalf of its customers. Yahoo recently pushed for declassification of its previously secret 2008 challenge, in the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court and Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review, to a government directive issued under the Protect America Act (the FAA’s predecessor statute). The Sunnyvale, California–based company also published 1,500 pages of litigation documents along with a promise to its users that it would “continue to contest requests and laws that we consider unlawful, unclear, or overbroad.” Apple closed a major security loophole in its mobile-phone software—with much fanfare(and concomitant apoplexy from law-enforcement officials). And in announcing its First Amendment suit, Twitter couldn’t resist hashtagging its own efforts, titling the blog post in which it announced the suit “Taking the fight for #transparency to court.”

This—technology companies’ efforts to compete on privacy by enthusiastically courting the public with demonstrations of their willingness to stand up to the government and inform the citizenry about the government’s actions—is undoubtedly a positive development. As my former ACLU colleague Ben Wizner recently told Guernica:

[O]ne of the great contributions that Snowden has made is to make some very powerful tech companies adverse to governments. When these companies and government work hand in glove, in secret, that is a major threat to liberty. But these tech companies, which are amassing some of the biggest fortunes in the history of the world, are among the few entities that have the power and the clout and the standing to really take on the security state.

One of the important ways in which technology companies have begun to assert themselves in this regard has been through so-called “transparency reports.” These reports provide the public with limited information about the kinds of law-enforcement and national-security requests the companies receive in a certain time period. The basic structure of the reports emerged from a series of lawsuits filed by several major companies (including Google, Yahoo, and Facebook—but not Twitter) in the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court in the fall of 2013. Prior to the lawsuits, the government had authorized the companies to publicize only the aggregate totals of surveillance requests received in a given reporting period—whether from state and local law enforcement for run-of-the-mill crimes, or from the FBI in national-security investigations. The companies sued, claiming that the government’s unwillingness to permit publication of more specific numbers amounted to an unconstitutional prior restraint under the First Amendment.

In January 2014, the companies and the government came to an agreement that permitted the companies to report the number of national-security requests they received in greater detail. Still, there is reason to question how useful the new reporting structure actually is. The companies can report the number of national-security requests only in bands of 1,000, ranging from 0–999, 1,000–1,999, and so on. They can issue reports only every six months, and with a six-month publication delay. Finally, companies can say nothing at all for two years about any order that is the first of its kind “served on a company for a platform, product, or service (whether developed or acquired)”—so-called “New Capability Orders.”

As mentioned, Twitter did not sign the January 2014 agreement (the “DAG Letter”)—and its newly filed complaint gives us a good idea why. Twitter repeatedly emphasizes that its central objection to the reporting framework to which its competitors agreed is that, “since the permitted ranges begin with zero, service providers who have never received an NSL or FISA order apparently are prohibited from reporting that fact.” Complaint ¶ 27; see id. ¶¶ 5 (“In fact, the U.S. government has taken the position that service providers like Twitter are even prohibited from saying that they have received zero national security requests, or zero of a particular type of national security request.”), 6 (“Twitter is entitled under the First Amendment to respond to its users’ concerns and to the statements of U.S. government officials by providing more complete information about the limited scope of U.S. government surveillance of Twitter user accounts—including what types of legal process have not been received by Twitter—and the DAG Letter is not a lawful means by which Defendants can seek to enforce their unconstitutional speech restrictions.”); see also id. ¶¶ 30; 39; 43; 47; 49. The company’s blog post likewise highlights the “zero” element.

This suggests that while Twitter is certainly arguing that the government’s restriction of surveillance-request reporting to large bands of 1,000 cannot be sustained under First Amendment strict scrutiny, the company’s primary objective is to win the right to say what sorts of orders it has not received. Why would Twitter care so much about “zero”? One likely answer is that because almost all Twitter posts are public (as opposed to email services like Gmail and Yahoo), the government has little national-security interest in the data stored on the company’s servers. Given the relative paucity of surveillance requests it receives relative to its Silicon Valley brethren, Twitter would like to distinguish itself by informing its users that it stands alone at “zero,” and not merely with other companies who have received “0–999” requests.

I’m not a legal expert or tech expert, but reading between the lines I would say your personal data is safe on TruthSocial but has already been scooped up by the Government if you’re on Facebook or Twitter!

That’s how I read it!

How about you?

Join the conversation!

Please share your thoughts about this article below. We value your opinions, and would love to see you add to the discussion!